By Bruno Rukavina

Over the past five years, we have hypothetically been witnessing a rise in chaos within international relations. In recent years, due to ongoing challenges, numerous authors and scholars in the Russian Federation have been warning about the collapse of the existing international order, which would be followed by a certain kind of chaos. Apart from Karaganov, Fenenko, and Trenin, who explain the breakdown of the order through various approaches and arguments, here we will focus on a Russian researcher who is perhaps less known in Croatia, Dmitry Gennadyevich Evstafiev (rus. Дмитрий Геннадиевич Евстафьев), who, in several of his articles and analyses, attempts to explain the concept of chaotization (rus. Хаотизация) in the contemporary world.

Chaos and/or Anarchy

The word “chaos” etymologically comes from the Greek language, signifying the primordial void or boundlessness (gr. Kháos). In philosophy, according to Plato and Anaxagoras, chaos denotes a formless primordial matter upon which the spirit has not imposed shape, while in everyday life, chaos is understood as confusion, disorder, and turmoil (Croatian Language Portal, 2025). In international relations, we much more frequently encounter the term “anarchy,” especially in the context of the realist theory of international relations. Anarchy is a structural characteristic of the international system, denoting the absence of a central authority or a superior power capable of establishing rules, enforcing laws, and punishing violators among states. According to realists, anarchy is precisely the main cause of conflict and the struggle for power, which should lead to a balance of power if states act as rational actors seeking security.

The key characteristics of anarchy in international relations are based on the fact that all actors, that is, states, operate as formally equal and sovereign entities. In such a system, there is no overarching authority, which means there is no global power with the ability to forcibly enforce laws, and there is no so-called “world police.” Therefore, each state must take care of its own security, relying on the principle of self-help. In such an environment, distrust prevails among states, and even current allies can be perceived as potential threats, as international relations are grounded in uncertainty, the desire for dominance, and insecurity. Ultimately, power becomes the key means of survival, whether it be military, economic, or technological power. Only through the accumulation and demonstration of power do states seek to secure their position and survival in an anarchic international system.

What, then, would be the difference between anarchy and chaos/chaotization in international relations? The term “anarchy” refers to the absence of a (global) authority possessing a monopoly over the use of force or legislation. In such a system, there is no “world government,” and states remain sovereign and formally equal actors, bearing the responsibility for their own security. Although anarchy is a state of lack of order, it does not necessarily imply chaos, as a stable order, a balance of power, and even institutional cooperation can exist within an anarchic system. Anarchy is essentially a neutral structure—a framework within which international relations occur without a centralized authority (such as through the balance of power). Nearly all major theories of international relations, including realism and liberalism, take anarchy as a starting point that influences state behavior.

In contrast to anarchy, chaos or chaotization refers to the process of the breakdown of existing structures, rules, and norms of behavior within the international system. It is a state of profound instability in which there is not only an absence of central authority but also a lack of mutually accepted rules of the game. Under such circumstances, institutions, norms, and rules weaken or lose legitimacy, hegemonic actors (such as the United States) lose control, and non-state actors, hybrid wars, grey zones, and asymmetric threats come to the fore. Beyond mere uncertainty, a chaotic system lacks consensus on common interests, respect for red lines (which are no longer respected by either those who cross them or those who should act when they are crossed), and adherence to rules and norms of behavior.

Authors dealing with this phenomenon include Zygmunt Bauman, who speaks of “liquid modernity” in which stability, structure, and long-term perspectives have disappeared, replaced by volatility, changeability, insecurity, and perpetual fluidity. In times of universal uncertainty, chaos becomes the structure itself (Bauman, 2000). Of course, contingency and fluidity may indeed be constants in our lives if we recall Heraclitus’ phrase Panta rhei—everything flows—and Ovid’s Omnia mutantur—everything changes. While anarchy is an (informal) structural constant in international relations, chaos represents a negative transformation of that anarchy, a state in which even the minimal (informal) stability that the anarchic system provides is lost. It leads to the chaotization of anarchy itself. In this sense, chaos signals the collapse of the international order and the entry into a phase of a kind of geopolitical/international entropy, with unpredictable consequences for security.

The Chaotization of the World from the Russian Perspective

Based on the analysis of the works and lectures of Dmitry Gennadyevich Evstafiev, a Russian political scientist and professor, it is possible to construct a systematic interpretation of the phenomenon of the chaotization of the world from the Russian perspective, highlighting a series of deeper strategic insights and critiques of the international order. Evstafiev approaches this issue not from the perspective of a general moral or ethical collapse (if one can even speak of any kind of moral/ethical system at the level of international relations), but from an analytical view of the clash of developmental micro and macro political-economic tendencies and logics in the world, as well as the change in instruments, aspects, and forms of power in international relations.

Evstafiev defines the period between 2017 and 2021 as the “pre-chaos” phase in which the world was gradually entering a new era of disorder/entropy/chaos. During this period, multi-layered political, economic, and technological logics of actors came to the fore on the global stage but had not yet been institutionally shaped. This “interzone” is characterized by initial unpredictability and the paralysis of existing international mechanisms, as no actor or institution succeeds in establishing a dominant order. For Evstafiev, chaos is not a condition that arises spontaneously, but a result of the conflict and competition between the developmental logics of opposing international actors, which are mutually incompatible. These modes of action—political, economic, and technological—attempt to shape a new international order but without successfully establishing universal domination. Such a clash produces the impression of global disorder (chaos), where the directions of development cannot be predicted in advance or rationally explained.

One of Evstafiev’s most important theses is that the West uses chaotization as a tool of geopolitical management in regions where it cannot achieve stable domination. Instead of open military intervention, it employs a “strategy of controlled chaos”: destabilization of local political systems through military threats, informational manipulation, and control over conflicts via local elites. According to Evstafiev, this method is applied in regions such as the Middle East, Sudan, Eastern Europe, and the Black Sea, where power is maintained without formal responsibility.

Evstafiev argues that states, particularly the United States, are abandoning normative models and increasingly manage through the perception of strategic strength and the (un)availability of certain options. This means that control over expectations and scenarios becomes more important than classical institutional regulation. States that do not belong to the so-called “collective West” face an existential choice: they can either develop their own institutions and regional centers of power (poles), that is, self-regulate by distancing themselves from the West, or they will be pushed into a wild world of external manipulation within chaotic regions. In the latter case, they become objects of other people’s geopolitics and arenas of chaotic management without their own sovereignty. Evstafiev therefore advocates for the geopolitical and geoeconomic emancipation of the “non-West.” Thus, Evstafiev views chaotization as a consciously employed method of political action by the collective West.

At the moment when soft power no longer functions, hard power is applied to restructure world spaces over which domination has not been established, and this is done without institutional obligations. Chaos, in this sense, does not occur “from below” but is generated “from above” as a tool of hegemony under conditions of shifting forces. According to Evstafiev, chaos is not a product of the collapse of the existing order but a consequence of an international vacuum (non-polarity) in which particular, competing logics collide without clear international institutions and rules/norms. The West, in this analysis, uses chaotization as an instrument/tool of power, while “non-Western” states are forced to choose: either to affirm themselves institutionally (develop their own institutional framework) or to be thrown into the spatial circle of chaotization (remain trapped in zones of chaos where they will remain objects of manipulation) (Evstafiev, 2023). Naturally, there is also a third option—to join and become part of the collective liberal-democratic West (which, in the case of Russia, the West itself did not want at the beginning of the 21st century and thus paradoxically became a co-creator of today’s Russia).

Dmitry Evstafiev’s analysis offers an alternative paradigm of geopolitical thinking, rejecting liberal assumptions about a universal order and advocating a (neo)realistic and strategic view of power, institutionalization, and the new international order in development. Evstafiev concludes in his texts and lectures that for Russia itself, the chaotization of the world does not signify only a risk or a challenge but also an opportunity, especially if the inevitability of chaotization is accepted (Evstafiev, 2023). At the center of chaos, there always lies opportunity, because where order ceases (or where it is challenged), possibilities begin.

For Russia, chaotization is perhaps even “a kind of everyday aporia (an impasse or insoluble problem) that has persisted since the end of the Cold War.” Russia has two choices: either, as a state that does not behave according to the (Western) rules in international relations, it will be characterized/labeled as a spoiler and for that reason will be subjected to economic-political sanctions because it defends its national interests against NATO expansion (the instrument/tool of American foreign and security policy), or it will, by crushing its material existence, submit to American interests, as was the case with liberalization in the 1990s.

A similar aporia for Russia existed in February 2022, when it could either watch as Ukrainian forces militarily took over the LNR and DNR or intervene militarily across Ukraine, which once again labels it as a spoiler and subjects it to economic-political sanctions. This aporia represents a perpetual foreign policy and security trap (Rus. ловушка) for Russia, with the Special Military Operation (or invasion/aggression) being part of that trap, from which Russia cannot exit except through ultimate victory, whether that ends in military victory or diplomatic negotiations. Because of this aporia, since the Cold War, Russia has mostly had a reactive foreign policy, always responding to Western actions, that is, making foreign policy and security moves second, rather than strategically creating them first” (Rukavina, 2024: 62).

Bruno Rukavina is a specialist in foreign policy and diplomacy and a PhD candidate at the Faculty of Political Science, University of Zagreb.

Originally published on Geopolitika.News: https://www.geopolitika.news/analize/rusija-ima-samo-dva-izbora-prijeti-nam-pakao-kroz-kaotizaciju-medunarodnih-odnosa-1/

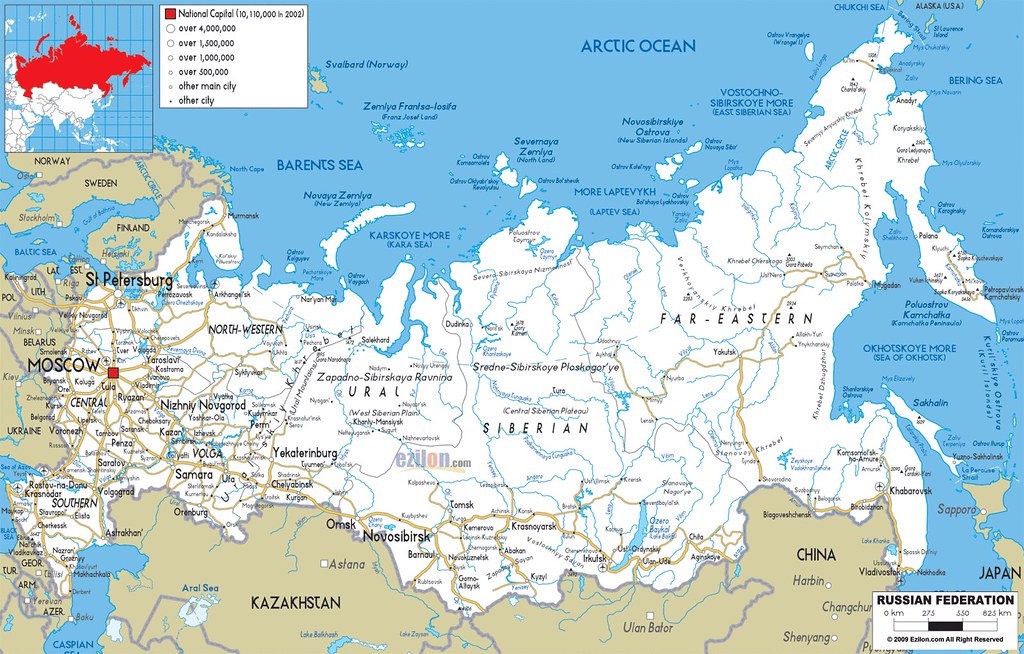

Covered image: Wikimedia Commons