By Matija Šerić

The time we live in is by no means favorable to the Islamic Republic of Iran. The tectonic shifts set in motion after Hamas’s incursion into southern Israel on October 7, 2023, are not in Iran’s favor. On the contrary. It is enough to mention just a few events to make it clear to anyone that today, life is not easy for the Iranian state or its ordinary people.

After Hamas’s reckless action, an Israeli-Palestinian war erupted in the Gaza Strip, resulting in the deaths of several tens of thousands of Palestinians. In 2024, Israel killed leaders of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Hamas, and Hezbollah in its air and drone strikes. Shiite Hezbollah in Lebanon was significantly weakened after its troops and infrastructure were bombed by Israeli forces. By a twist of fate, a plane crash also claimed the life of President Ebrahim Raisi.

An Unfavorable Sequence of Events Threatens Iran

The culmination of misfortune in 2024 occurred in December when Assad’s regime in Syria was overthrown. In the current year, Iran was subjected to bombings not only by Israel but also by the United States. Although the formal targets were military and nuclear facilities, in a 12-day war in June, just over a thousand people were killed (including 140 women and children), and more than 5,800 civilians were injured. Estimates indicate that the airstrikes killed over 30 high-ranking Iranian security officials and at least 11 nuclear scientists. This was a major blow to Iran’s security apparatus. And that was not all. The saying “When it’s not your day, it’s not your day” proved true.

As the “icing on the cake” of misfortune, a prolonged drought followed, posing a serious threat to Iran. Its population of 92 million people has been experiencing intermittent electricity shortages (from two hours per day upwards) since the end of July, and shortages of water and food may also occur. If the current negative trends continue, Iran could face hunger and thirst, putting the Shiite regime in an unenviable position.

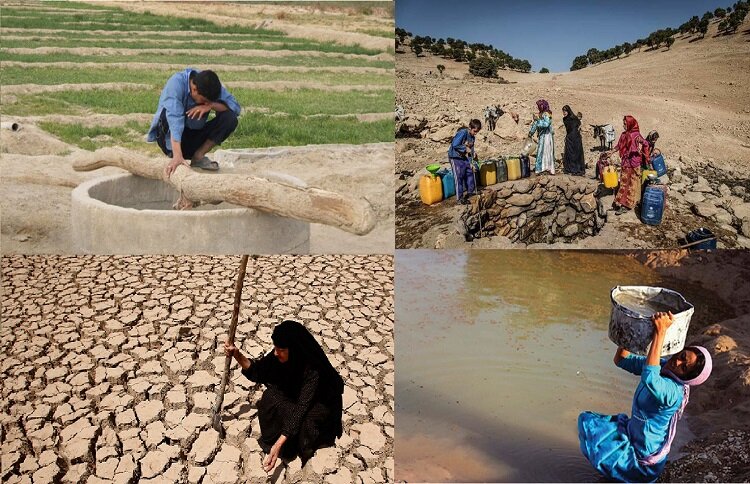

Continuous Drought Has Created a Crisis

In recent years, Iran has been exposed to a continuous drought, most severely affecting the central and eastern provinces. The situation has worsened. In the past four months, rainfall has decreased by 40 percent. The current drought has deepened Iran’s long-standing water crisis. Beyond drought, the water crisis is a result of excessive groundwater depletion, poor management of irrigation systems, and insufficient investment in infrastructure. The synergy of all these factors has put Iran in a dangerous situation. Reservoirs in lakes and rivers have dropped to historically low levels.

According to the latest research, about 28 million Iranians currently live in areas affected by severe water shortages. National reservoirs are at 46 percent capacity, and seven key dams have supplies below 10 percent. More than 40 cities regularly face water supply restrictions, while at least 19 provinces experience a severe lack of water. The most striking indicator of the crisis is Lake Urmia, once the largest saltwater lake in the Middle East, which has lost as much as 90 percent of its volume since the 1970s.

Authorities Acknowledge the Seriousness of the Situation

Official Tehran is increasingly acknowledging that it is approaching a critical point in managing water resources. On July 31, President Masoud Pezeshkian warned of an acute water crisis: “In Tehran, if we fail to manage consumption and if people do not cooperate in limiting it, by September or October there will be no water in the dams.” Amid record-breaking heat and a worsening water supply crisis, the Iranian government was forced on August 6 to declare a one-day national holiday to save electricity and water. Temperatures in Tehran exceeded 40 °C (104 °F), and authorities advised citizens to stay indoors during the hottest hours. During the heatwave, one-day closures of offices and banks were also implemented.

Extreme heat is putting heavy strain on Iran’s electricity grid, especially hydroelectric plants, which account for about 15 percent of the country’s total electricity production. This has led to electricity rationing. While there have been no water shutdowns, Tehran’s public water company has reduced water pressure in the supply system to curb consumption, and households with above-average water usage are facing significant price increases. Tehran’s 10 million residents are major consumers.

“Zero-Day” Scenario Cannot Be Ruled Out

The government is considering implementing rationed water consumption for the largest users: industry, agricultural complexes, and wealthier urban districts. This demonstrates that water shortages in Iran are no longer a distant threat but an imminent reality. In Iran, the so-called “Zero-Day” scenario—when city taps might run dry—is increasingly being discussed. Although some state officials claim it is merely planning for potential emergencies, the very fact that such a possibility is being considered indicates the severity of the crisis.

Farmers—The Biggest Losers

Due to the severe drought, Iranian authorities have decided to reduce domestic agricultural production (agriculture accounts for 80 percent of domestic water consumption) and significantly increase wheat imports in the first quarter of 2026. Recently, on August 17, Ataollah Hashemi, head of the Iranian National Wheat Growers’ Union, announced that domestic wheat production is seeing a serious decline: from April to August, production fell by about 5 million tons, or 31%, currently totaling 11 million tons. Consequently, state procurement of domestic wheat has also fallen—by 4.4 million tons, or 36%—to 7.6 million tons.

These indicators highlight the worsening situation in domestic agriculture, further increasing the need for foreign imports. According to forecasts, Iran will import around 4.5 million tons of wheat by the end of March 2026. The decline in domestic wheat harvests is primarily due to drought affecting wide areas across the country, but also because state purchase prices for wheat were lower than market prices, discouraging domestic producers. By comparison, the situation in neighboring Syria is even worse. There, production has fallen by 40%, and the authorities lack sufficient funds to buy wheat abroad. Iran, for now at least, has more money to purchase wheat to feed its growing population.

Government Measures for Stabilization

In the short term, the government aims, through the described water rationing and reduced agricultural production, to ensure at least minimal water supply for all. In the medium term, the government seeks to implement the Taleqan–Tehran water diversion project. This project plans to bring water from the Taleqan River reservoirs to the capital to alleviate shortages. The government is fast-tracking the first phase of the project while promoting modernization of irrigation systems in agriculture.

The Shiite Regime Has Been Shaken

For the Iranian government, which is simultaneously striving to maintain political legitimacy and economic stability, the multi-dimensional water crisis is becoming a major threat with uncertain political consequences. The “axis of resistance” against Israel and the U.S., led by Iran and its partners (Hezbollah, Hamas, the Houthis, and others), has been severely weakened after the events of the past two years. After many years of stability and sustainable development, Iran has become vulnerable, unstable, and exposed to external attacks.

Water crisis compounds power outages in Tehran

Despite Problems, the Regime Retains Popular Support

However, this does not mean that the Shiite theocratic regime will collapse, as suggested by many Western media outlets. Life in Iran is still largely proceeding normally. Although inflation in June was 34.5%, the situation is not apocalyptic. Tourists continue to arrive. However, if Iran runs out of water and possibly food (leading to famine), mass protests and street clashes could occur. That said, mass emigration is more likely than armed rebellion, as people in extreme situations prioritize survival.

Even in the event of an anti-government armed uprising, a regime change would not be easy. Over the past 40 years, ruling Shiite structures have built a robust intelligence and security apparatus, military, and education system. Additionally, they have the support of the more conservative social layers (especially rural populations), whose daily life has for millennia been rooted in traditional Islamic principles and Persian culture, which highly values peace, hospitality, and tradition. Under such conditions, pro-Western insurgents would struggle to gain support outside major cities, and Iran is primarily a rural country of mountain ranges, forests, plateaus, and fertile valleys. Whoever controls the rural areas, controls Iran.