By Matija Šerić

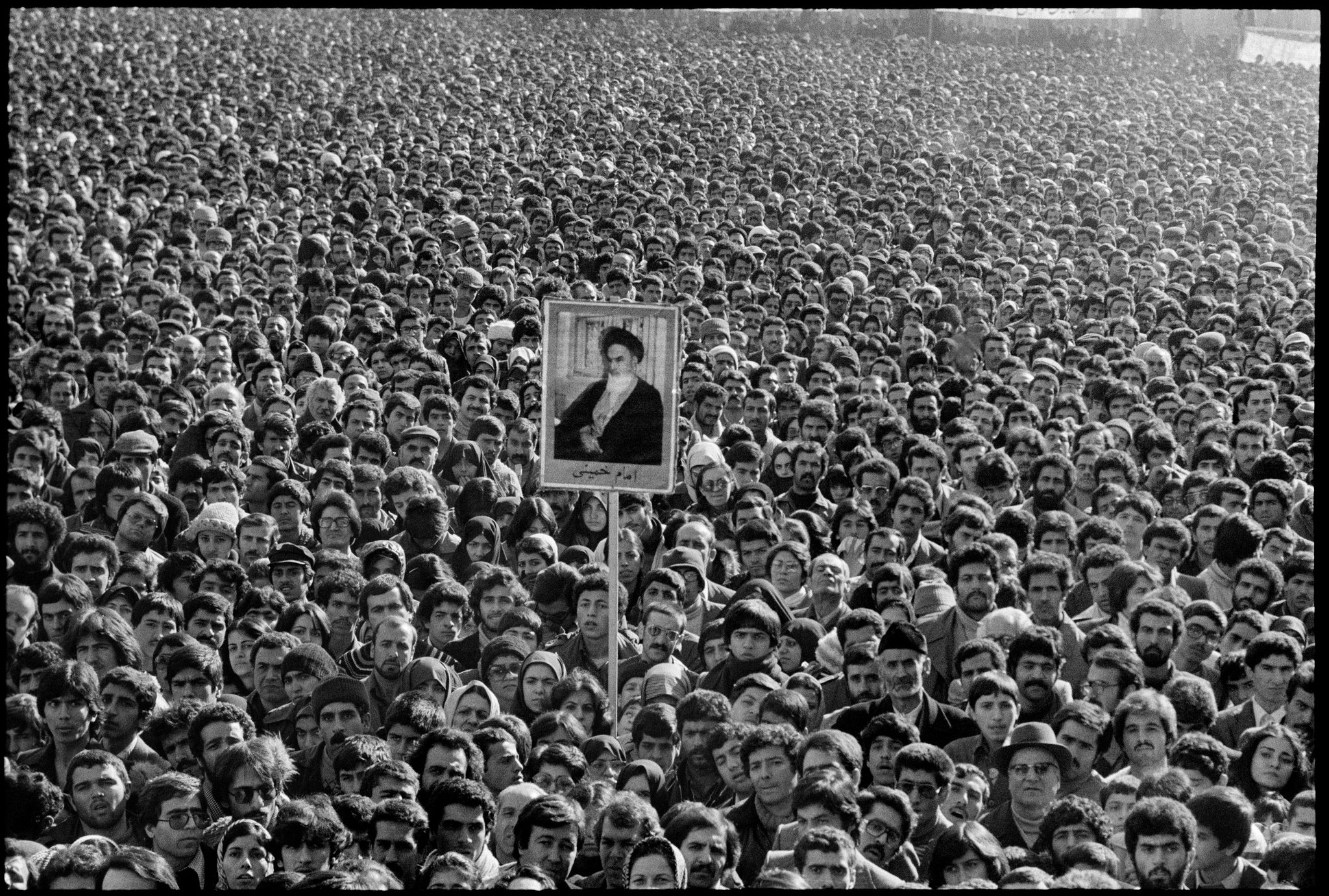

The Iranian Revolution strengthened resistance in the Third World to the dominance of both the United States and the Soviet Union. Although since the end of the Second World War the Left had been the main force opposing the United States, Khomeini’s return to Tehran and the Islamic Republic of Iran that he began to establish presupposed the existence of an alternative focal point of opposition in which worldly justice is derived from the word of God, rather than exclusively from human decisions. Islamism offered an ideology focused precisely on the Third World, through which it was possible to condemn both Western projects of modernization.

The Revolution’s Meaning for the Cold War

While the revolution was at its height, a Tehran student activist emphasized in an interview: “Imperialism exploits us and dominates the whole world. Imperialism wants to turn everyone into its servant and to rule over all. America would like to bring the Iranian state and people under its control. On the other hand, the Islamic Republic is inclined toward all free and independent governments that stand for justice. This is the kind of rule people wanted and created themselves; this government is a friend of freedom and an enemy of imperialism, communism, and all similar things. Countries like America do not give freedom to those who need it and are inclined only toward the class that has ruled over them.”

However, although they condemned Western modernism, Iranian Islamists carefully avoided condemning the technology and organizational methods that modernism entailed. Khomeini never stopped repeating that Muslims must open up access even more and increase their understanding of contemporary development, while at the same time not allowing material goods to dominate their thinking. Scientific progress had to be harnessed to serve Islam.

Iran and America

For Khomeini’s new regime, confronting the U.S. and the USSR (especially after the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan) was a key confirmation of its own revolutionary and religious righteousness. In a message to pilgrims departing for Mecca in September 1980, Khomeini called on all believers to show international solidarity and readiness to sacrifice for their faith: “Neutral countries, I call on you to bear witness to how America is preparing to destroy all of us. Wake up and help us achieve our common goal. We have turned our backs on both East and West so that we may govern our country ourselves. Do we therefore deserve to be attacked from both East and West? Bearing in mind the existing conditions in the world, the position we have won is a historical exception, but if we die, enter martyrdom, or suffer defeat, our achieved goal will not be lost.”

Despite Khomeini’s fierce anti-American rhetoric, many members of the Carter administration still believed that it was possible to find some modus vivendi with the new Iranian regime. Expecting that the main challenge to the American agenda would come from the Left, the CIA and Iran specialists in the National Security Council continued attempts to establish channels of communication with Khomeini’s inner circle—until a group called the “Students Following the Imam’s Line” seized the U.S. embassy.

The Disappearance of Illusions About U.S.–Iran Cooperation

Only when Khomeini openly supported the occupation of the building and then the holding of the embassy staff as hostages—responding to the Shah’s arrival in America—did Washington realize that the Islamists were an even more irreconcilable enemy of the United States than the communist Tudeh Party and the rest of the Iranian Left. Carter’s failed military rescue operation confirmed the powerlessness of the U.S. in post-revolutionary events and gave Khomeini an excellent opportunity to push all his domestic rivals to the margins in the name of an external threat to the revolution.

Iran and the Soviet Union

Over time, the Soviet view of the Iranian Revolution in many ways resembled the American one. In the eyes of the International Department of the CPSU Central Committee, Iran had been among the top countries ripe for revolution since 1945. The USSR maintained close ties not only with Tudeh and the Left but also with the moderate Islamic opposition. At first, Moscow expected that the 1977–1978 crisis would yield the replacement of the Shah’s autocracy with some form of nationalist constitutional government like Mosaddegh’s. When by late 1978 it became clear that Mohammad Reza would step down and strikes spread, the International Department began to believe that Tudeh might get a real chance to influence Iran’s future political life and conditions.

Moscow recommended—and Tudeh followed—a strategy of close identification with the Ayatollah as the revolutionary leader. In a special statement, the Tudeh leadership denied that it intended to “immediately build socialism,” but announced that it intended to “consolidate anti-imperialist achievements.” “It is perfectly clear that anti-imperialist forces are active under Khomeini’s leadership,” the statement continued. “Therefore, the most important forces of the Iranian Left and of Tudeh… stood behind Khomeini.”

Two Soviet Approaches to the Iranian Question

By mid-1979, two very different approaches to the Iranian question emerged in Moscow. According to the gradual approach—advocated by the head of the International Department, Boris Ponomarev, and by the leader of the majority in the Politburo—the Iranian Revolution was an anti-imperialist movement that would, over time, turn to the Left in search of political direction. In the meantime, the most important thing was to avoid a counterrevolution that the U.S. might provoke.

The other main approach, promoted by KGB chief Yuri Andropov, assessed that in the foreseeable future the mullahs would hold the reins of Iranian politics, and that Tudeh was too weak and too divided to gain greater influence. At best, the USSR could hope for some form of settlement with Khomeini under which the Iranian leader would soften his rhetorical attacks on the Soviet Union, refrain from intervention directed against the communist government in neighboring Afghanistan, and would not create “difficulties” for the “anti-imperialist policy” of the USSR’s main regional allies, Iraq and Syria. The arrival in Tehran of KGB veteran Major General Leonid V. Shebarshin as rezident aimed to ensure that the Soviet leadership would receive sufficient intelligence information to choose between the two approaches—and also to understand that the two views did not necessarily have to be contradictory.

Brezhnev’s Insight Into the New Iran

The duality of views among his advisers regarding the Iranian Revolution also influenced the outlook of the CPSU General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev. In a conversation with East German leader Erich Honecker in early October 1979, Brezhnev warned of “tendencies of a not particularly positive nature” in Soviet–Iranian relations, stressing that “our initiatives regarding the development of good-neighborly relations with Iran are currently not producing any practical results in Tehran.”

He also complained about the Ayatollah’s campaigns against the Left and the persecution of national minorities. “All of this is known to us,” Brezhnev said. “But something else is also clear to us: the Iranian Revolution has undermined the military alliance between Iran and the U.S. When it comes to a whole range of international issues, especially regarding the Middle East, Iran now takes anti-imperialist positions. Imperialism is trying to regain influence in the region. We seek to resist these efforts. We are patiently working with the current Iranian leadership and winning them over to develop relations on the basis of equality and mutual benefit.”

Soviet Officials Read the Iranian Authorities Well

After the outbreak of the hostage crisis in November 1979, Shebarshin’s reports to Moscow became increasingly negative. While the Soviet ambassador in Tehran, Vladimir Vinogradov, interpreted Khomeini’s approach as hostile to Moscow but cautious out of fear of clashing with both superpowers at the same time, the KGB rezident perceived it as ever more openly hostile. Shebarshin’s reports spoke of three scenarios: (1) the Americans would carry out a successful operation to overthrow the regime; (2) Khomeini’s reactionary followers would take power and overcome differences with the United States; (3) the Ayatollah would remain in power, but antisovietism within him would grow stronger and he would begin inciting Muslims to revolt throughout the entire region. It turned out that in some ways both Vinogradov and Shebarshin were right.

Although he never abandoned his public condemnations of communism and the USSR as the “other great Satan,” Khomeini always took care to avoid an open conflict with the Soviets. All the positive goals Moscow set regarding Iran proved to be mere fantasies. Moscow’s failure to dissuade its ally Saddam Hussein from attacking Iran in September 1980 also meant that the Soviet desire to establish a regional anti-imperialist front would not be realized.

The Collapse of Tudeh

The KGB’s methods of constant intelligence gathering contributed to the collapse of the Tudeh Party. Under the pretext that its members were Soviet spies, the Islamists crushed the Iranian Communist Party. Several thousand communists were arrested, and hundreds executed. As a gesture of goodwill toward the Soviets, the lives of the main party leaders were spared; however, while in prison, many of them converted to Islam—an indication of the ideological collapse of Iranian communism. General Shebarshin was expelled, but soon afterward, at the KGB’s Moscow headquarters, as head of foreign intelligence departments and operations, he got the opportunity to spread his anti-Islamic views widely.