By Matija Šerić

In mid-January 1978, riots broke out in Tehran and other cities. Protesters carried banners and chanted slogans labeling the Shah a traitor while celebrating the exiled Ayatollah Khomeini as an example of patriotic integrity and honesty. Many of the protesters were young people and students, angered by comments about the Ayatollah published in the Tehran newspaper Etella’at. Alongside students and youth, unemployed people who had migrated from rural areas to the cities also took part in the protests.

The Pahlavi Revolution Comes as a Surprise

Pahlavi, weakened by years in power and by illness, was stunned by the outbreak of open hostility toward his rule. He wavered between concessions and repression, convinced that the protests were part of a broader international conspiracy against him. Initially, the Shah continued his program of liberalization and preferred negotiating with protesters rather than using force. He promised that democratic elections would be held the following year. Censorship was relaxed, and a resolution was issued to curb corruption in the government and state administration. Protesters were soon released from custody.

The police forces were not adequately trained to control demonstrations, so the army assumed that role. It was instructed not to use “lethal force,” although inexperienced soldiers sometimes exceeded these limits, which only poured fuel on the already heated atmosphere.

The Deceptive Summer of 1978

By the summer of 1978, protests had stagnated. They remained subdued for four months. Around 10,000 participants in each major city (with the exception of Isfahan, where protests were larger, and Tehran, where they were smaller) demonstrated every 40 days. This represented a significant minority relative to the total population. Although tensions persisted, at the beginning of summer it appeared that the Shah’s policy of crisis management was succeeding. CIA analysts concluded that Iran was neither in a pre-revolutionary nor a revolutionary state. Such misjudgments are considered among the CIA’s greatest strategic failures since its founding in 1947.

The Fateful 19 August

On 19 August, in the southwestern city of Abadan, four arsonists blocked the exits of the Cinema Rex movie theater and set it on fire inside. This was the deadliest terrorist attack in history prior to September 11, 2001, and the attacks on New York’s Twin Towers. A total of 422 people burned to death inside the cinema. Ayatollah Khomeini immediately blamed Pahlavi for the incident, while the authorities blamed Islamists. Due to the prevailing revolutionary atmosphere, the public held the regime responsible for the fire despite the government’s insistence that it had no involvement. Tens of thousands of protesters flooded the streets chanting “burn the Shah” and “the Shah is guilty.” To this day, the true perpetrators of the fire have not been conclusively identified.

“Black Friday” in September Changes Everything

However, no concessions could save the Shah’s regime any longer. Public anger boiled over, and society was ready to overthrow the Pahlavi establishment. Although the Shah’s police temporarily restored control, renewed protests in Tehran in September 1978—during which security forces killed hundreds—demonstrated that the streets were slipping beyond the state’s control. The most tragic event was “Black Friday” on 8 September, when around 100 people were killed and more than 200 injured at Jaleh Square in Tehran. This event was pivotal in the Iranian Revolution, as it ended any “hope of compromise” between the protest movement and the regime. The September protests also showed that left-wing and moderate Islamist circles, together with the Islamist opposition led by Khomeini as its most prominent symbol, had united against the Shah.

A Feeble American Response to the Islamic Revolution

For American experts on Iran, the left—not the Islamists—continued to represent the greatest threat. It seemed unlikely that the two camps would draw closer. As the State Department had concluded during the last major crisis in 1963: “Communist propaganda shows, on the one hand, anti-religious sentiment, and on the other tolerance toward the Shah’s reforms; the mullahs are traditionally hostile toward Russia and communism.”

American policymakers therefore viewed the Iranian Revolution within a broader Cold War framework, in which any threat to the Shah’s regime would benefit the communist Tudeh Party. Moreover, Tudeh appeared as the bearer of an alternative concept of modernity and, unlike the “reactionary” Islamists—who in Washington were seen solely as a negative force—could govern the country. Although the Americans attempted to establish contacts both with the moderate Islamic opposition and with Islamists, Khomeini firmly rejected these efforts. The CIA and the U.S. embassy concluded that America had no choice but to continue supporting the Shah.

Khomeini Makes His Move

After being expelled from Iraq by Saddam Hussein’s regime—a humiliation he never forgot—Khomeini, in the autumn of 1978, began issuing instructions to the Iranian opposition from his new place of exile, this time in Paris. Through messages distributed on cassette tapes and videotapes, the Ayatollah called on the people to continue strikes and protests and urged the army to rebel against the infidel government. Khomeini also began shaping a broad political program in which words such as independence, democracy, and freedom played a prominent role—albeit with the addition of the adjective “Islamic,” as a form of clarification and moderation.

Opposition figures of all political orientations began flocking to Khomeini in Paris, contributing to the impression that the Ayatollah had placed himself at the head of diverse and broad forces resisting the regime. However, these associates had little influence on Khomeini’s ideas about the state he envisioned building as an Ayatollah. On the contrary, he was often appalled by their secularism and would reprimand them, urging a return to the path of true Islam. Only by returning to that path, Khomeini believed, could they become an integral part of the revolution.

The Overthrow of the Shah

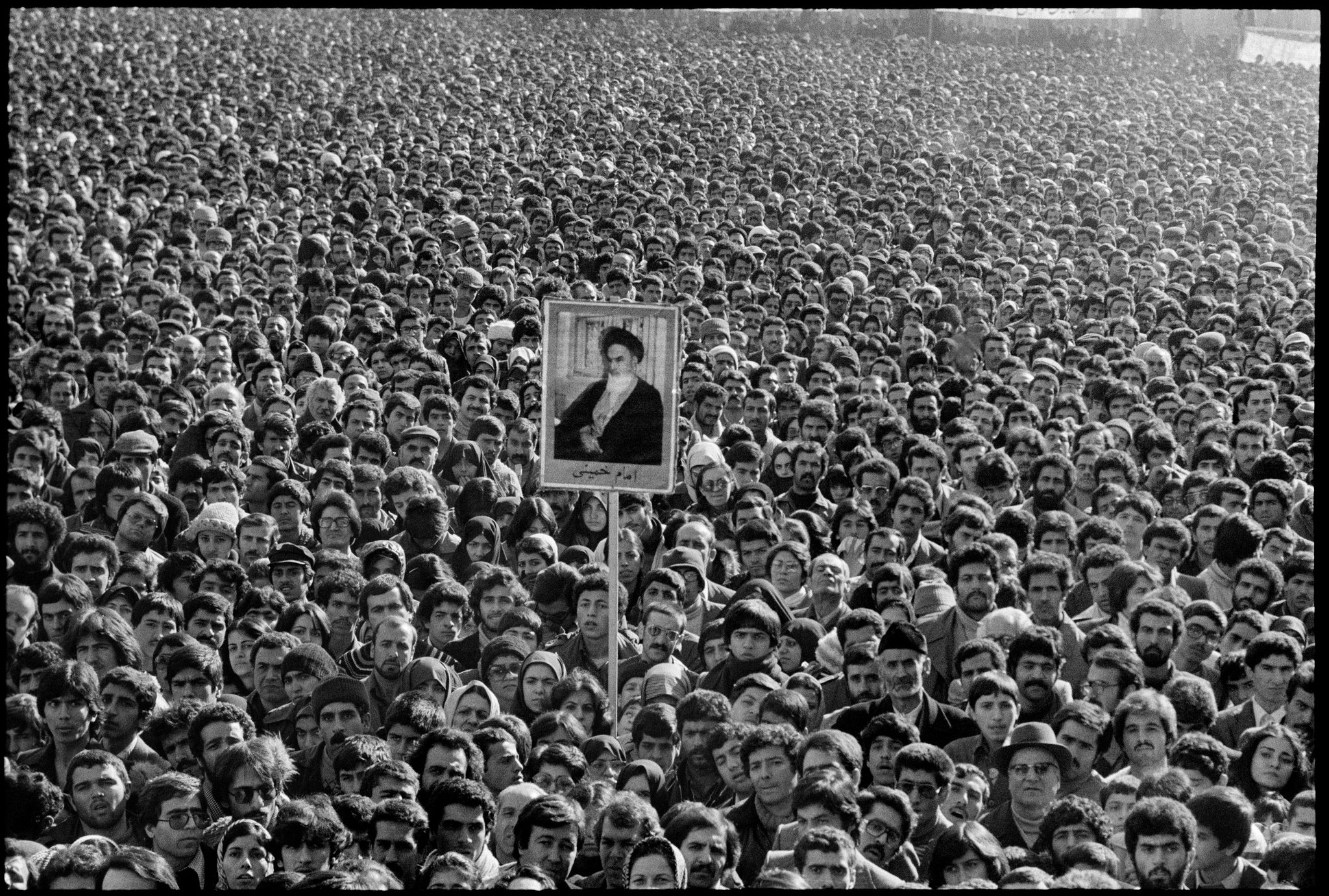

The Shah’s government collapsed in December 1978 when one million people marched on Tehran demanding the overthrow of the monarch and the return of the exiled Ayatollah. The marches took place during Ashura, the two most important days of the month of Muharram, when Shiites commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Husayn in the 7th century. Protesters’ slogans were filled with symbolic meanings centered on sacrifice and purification—words that had dominated previous protest gatherings and that Khomeini wished to hear. The marches during the month of Muharram were not only a powerful symbol of the dominance of Islamic discourse within the opposition but also revealed the complete impotence of the Shah’s authority.

The Return of the Ayatollah

Reza Pahlavi left the country on 16 January 1979 and never returned. The last government appointed by the Shah, led by the Mosaddeghist nationalist Shapour Bakhtiar, soon began transferring an increasing number of its powers to the Islamic Revolutionary Council appointed by Khomeini. On 1 February 1979, the Ayatollah triumphantly returned to Tehran, where many ordinary Iranians greeted him as the Imam—a descendant of the Prophet who had returned to redeem his people.